La Fayette, We Are Here!

La Fayette, We Are Here!

Napoléon Part II - From Paris to Saint Helena

December 2nd 1804, Napoléon Bonaparte is crowned Emperor of the French. Over the next decade, he will keep reforming and modernizing France, but he will also fight the rest of Europe. He will become master of the continent, defeating all his enemies on land, only to go too far and to see Europe strike back at him and at France.

This is the second part of Napoléon's great adventure. If you haven't already done so, I encourage you to listen to the first part as well as to my episode on the French Revolution. Let us follow Napoléon and the Grande Armée on the battlefields of Germany, Poland, Russia, Spain and France. And then we will land on a tiny island, on the middle of the Atlantic. The Napoleonic adventure is one of strong contrasts, as you shall see.

Timecodes:

Introduction

04:20 - From Consul to Emperor

12:40 - The First French Empire and the Grande Armée

24:04 - The Fourth Coalition War and the Continental System

31:48 - The Peninsular War and the Fifth Coalition

44:02 - The Beginning of the Downfall: Russia

50:50 - Europe Strikes Back

1:00:00 - The Exile on Saint Helena

1:03:23 - Conclusion

Music: Marche pour la cérémonie des Turcs, composed by Jean-Baptiste Lully, arranged and performed by Jérôme Arfouche.

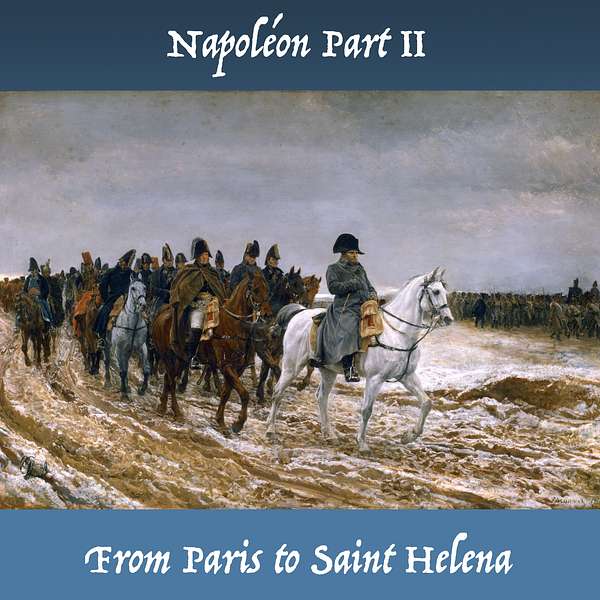

Art: 1814, Campagne de France, by Ernest Meissonier

Reach out, support the show and give me feedback!

You are walking on an edgy rock, watching the waves break themselves at its base. The wind is strong, as is the smell of the sea. There is nothing to admire in any direction, except more ocean, occasionally broken by the sight of a British frigate. You gaze at it with all your hatred, but know that you are stuck on that rock, incapable of doing anything about it.

You were born on an island, albeit a much more beautiful one. One nicknamed the île de beauté, the Island of beauty. That was 50 years ago. An eternity ago. During this half a century you’ve fought dozens of battles, defeated incredibly strong enemies, restored order in a torn apart country. But you’ve also experienced defeat, humiliation and treachery.

From one island to the other. This is how one could entitle your biography. Born in beautiful Corsica, only to die on the lonely rock that is Saint Helena. To have been the master of Europe, the most powerful of men, and to end up exiled, defeated, sick and far from your family.

Napoléon, oh Napoléon… Your story is one of tremendous contrasts. I shall tell its second part here. The one that saw you and your country take over Europe, only to see it strike back with a vengeance.

Welcome to "La Fayette, We are Here!", the French history podcast for the American public. I am your host, Emmanuel Dubois, and today we are talking about Napoléon. This is the second and last part of this series, I encourage you to listen to the previous episode where I discussed Napoléon's youth, first military accomplishments and rise to power. In this episode, we will study the years from 1804 until his death, in 1821.

We left Napoléon as First Consul of the French Republic, for life. As I have said in the previous episode, Napoléon is busy reforming France and her institutions. He also worked to make his own power greater and long lasting. On many levels, the Consulate is a Golden Age for France, with a stability came economical prosperity. The profound reforms and improvements spearheaded by Napoléon make France a modern country, probably the most modern in the world in many ways. France as it is today owes a lot to the Consulate period, whether the French know it or not. This period of peace and prosperity was a promise of Napoléon when he took power in 1799, and he had delivered. This will be the basis on which the next several years will be built and fought.

From Consul to Emperor

Under Napoléon's de facto dictatorship, under the pretence of democratic republicanism, the executive authority is greatly reinforced, the State is centralized and Napoléon's personal prestige and authority are without any contest. Being First Consul for life, he considers himself to be the equal of the other rulers of Europe, almost all hereditary monarchs. However, they do not seem him as their equal, rather as an opportunistic general, a grunt who got lucky. Napoléon grows aware of this in 1803-1804 and starts to devise a plan to alleviate it. He also faces another problem: succession of power. If he were to die or to retire, who would take charge? There could be elections, rigged ones of course, but he could not control the outcome. That was unacceptable for Napoléon and on March 27 1804, he proposes to make his position hereditary under a new system. On May 18, he is proclaimed Emperor of the French by the Sénatus-consulte with the Constitution of Year XII. It will be reinforced by a plebiscite in June 1804, where Napoléon gets 99.93% of support from the voters... Needless to say that was not the ideal fair election, but I also think it's fair to say Napoléon did have tremendous support within the population, especially the voters, who saw their situation improve greatly over the last few years, in part thanks to him.

Note the choice of words. Napoléon is Emperor of the French, not of France. He rules over a people, not a geographical area. Also, his power is not based on Divine Right, like the Bourbons before him. He considers himself to be the successor of Charlemagne, not of Louis XVI. He tries to distantiate himself from the monarchy and, technically, the Empire remains a Republic. He often refers to the beginnings of the Roman Empire and the reign of Augustus to make his point. I'll give you a concrete example, the first article of the new constitution states quote: "Le gouvernement de la République est confié à un Empereur qui prend le titre d'Empereur des Français." Or in English" : "The government of the Republic is entrusted to an Emperor who takes the title of Emperor of the French.", end quote. I've already stated that Napoléon tries to be a bridge between the Old and the New Regimes, to move forward while acknowledging the past, contrary to the hardcore Jacobins who wanted to make it disappear. This is further proof of this.Ironically, Napoléon sends for many members of the former staff of Versailles to come work for him. They know the etiquette, the protocols and every other details needed for him to be a proper Emperor. On December 2nd 1804, he is sacred Emperor by Pope Pius VII in the Notre-Dame cathedral. He actually took the crown and put it on his own head. He then proceeded to put a crown on Joséphine's head, making her Empress of the French. Napoléon is now 35 years old and his rise to power has been incredibly fast, efficient and remarkable.

Let's digress a bit to talk about Napoléon's inner circle. First, Joséphine, his wife since 1796. Their relationship has proven...difficult. Both of them had many affairs and Napoléon, although deeply in love with her at the beginning, has been considering divorcing since 1799. But he's actually very infatuated with Joséphine's children, Hortense and Eugène, and renounces the idea, for now.

During the Consulate, Josephine takes an active part of Napoléon's public endeavours. Although she never has any real power per se, she does accompany him and advise him. She also has links with old French noble families, even some who went abroad, and this helps Napoléon to figure out who is doing what in the Republic. By making her Empress in 1804, he leaves no doubt as to how central her role is, to the dismay of the women of his own family. His mother and sisters absolutely hate Joséphine. He actually made his sisters carry his wife's imperial coat during the ceremony. Aaaah, family troubles, always entertaining. Beyond the infidelities, the big problem that the couple faces is the lack of child. After nine years of marriage, they still hadn't any. Napoléon was growing more and more desperate to have heirs. Joséphine, now aged 41, seemed less and less likely to be the solution. This issues will come to a head in 1809, but we'll circle back to that.

Now, let's not forget who Napoléon is: a soldier. He gained his fame trough military actions, but he wasn't alone when he did it. Other officers fought alongside him. Many distinguished themselves multiple times on the battlefield. Some became close personal friends. In 1804, Napoléon finds a way to thank those he finds the most meriting: the Marshalate. The title of Maréchal de France, or Marshall of France had already existed, but had been abolished in 1793. It was reinstituted by the new Constitution and Napoléon used it to reward those he thought deserved it. Let me state the original Marshals of the Empire: Pierre Augereau, Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, Louis-Alexandre Berthier, Jean-Baptiste Bessières, Guillaume Marie-Anne Brune, Louis Nicolas Davout, Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, François-Christopher Kellermann, Jean Lannes, François Joseph Lefebvre, André Masséna, Bon Adrien Jeannot de Moncey, Édouard Mortier, Joachim Murat, Michel Ney, Catherine-Dominique de Pérignon, Jean Mathieu Philibert Sérurier and Jean-de-Dieu Soult. Others will be added through time, namely Victor, Macdonald, Marmont, Oudinot, Suchet, Gouvion-Saint-Cyr, Poniatowski and Grouchy. These names are a famous or infamous part of the Napolenic adventure, and I thought it fair to at least enumerate them.

The First French Empire and the Grande Armée

Europe had been at peace since the Treaty of Amiens in 1802. Nevertheless, France and Britain had been trading economic blows since 1803 and the temperature was rising between the two powers. In 1803, Britain declares war to France, in an effort to alleviate growing French economic dominance on the continent. The British use their main advantage, the Royal Navy, to great effect, taking French colonies and possessions abroad. France even finds allies, Spain for example who declares war on Britain in 1804. It's the beginning of a naval back and forth that will culminate at Trafalgar in October 1805, but we'll come back to that soon.

Understanding that they cannot defeat France alone, the British work to mount a new Coalition against France. It's a very complex process with lots of diplomacy involved. But to reduce it to the basics: the British are paying other countries to wage war on France. Britain had two advantages over France: the Royal Navy and money, and she used both widely and mostly wisely. During the next decade, Great Britain will bankroll all the coalitions against France in an important proportion. Conservative monarchies were too happy to be financed to fight their common and disturbing enemy. Make no mistake, there was an ideological part to the Napoleonic wars, but I believe it was more on the old monarchies side. Their conservative ways could not bear to accept France’s Revolution nor its predominance. But as we shall discuss later on, they will only manage to slow down the clockwork of change, not to stop it forever.

By October 1805, Britain, Russia, Austria, Naples and Sweden are allied against France, Spain and a few German kingdoms and duchies. On paper, the Coalition outnumbers France's forces completely. But Napoléon has a surprise for his enemies. Since 1802, he'd been working at completely rebuilding the army. It had undergone its deepest transformation ever. This new structure, complete with a versatile and efficient Corps system, will be called by Marshal Berthier the "Grande Armée".

This new army of around 200,000 men was assembled first in Northern France, with the potential objective of invading England. It was articulated around the new Corps System. Although Napoléon didn't invent the system, he was the first to implement it on a large scale. Along with Berthier, his chief of staff, they divided the Grande Armée in seven Corps, nicknamed the Seven Torrents. In campaign, each corps could march independently from the others, allowing a greater flexibility. They would always be at close range however, to reassemble quickly in case of battle. This would allow Napoléon to move enormous armies in enemy territory in record time. He would surprise his enemies times and times again with his speed and precision. This system will eventually be copied by most European armies by 1812, and it will remain in use until 1945.

The second half of 1805 is a game of movement on the seas for the French and British navies. Admiral Villeneuve roams over the Atlantic, hoping to force the British to a fight where he would have the advantage. Napoléon also hopes that enough British ships would leave the Channel to allow a French invasion. Both objectives fail. On October 21st 1805, the British Navy under Admiral Horacio Nelson, attacks the Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar. It is a complete victory for the British, despite the death of Nelson during the battle. The French and Spanish fleets are almost annihilated and British supremacy on the seas was now assured for the rest of the conflict. It will remain so for the rest of the century actually. The Royal Navy, better financed and trained was simply superior to the Franco-Spanish fleet.

But Napoléon was also on the move. On September 10th, Austria had attacked Bavaria, a French ally. Realizing what was going on and seeing an opportunity, Napoléon reacts quickly and decisively. He abandons his plan of invading the British Isles and heads east.

The corps system works brilliantly and the French army moves with remarkable speed. He forces the Austrian general Karl Mack to a unfavourable defensive position at Ulm, in Bade-Wurttemberg, on October 15th. The French outnumber the Austrians and completely crush them. On October 20th, they capitulate, having lost over 4,000 dead and 25,000 prisoners. The French had around 500 dead. However, their Russian allies are also on the move, trying to unite with the rest of the Austrian army to strike at Napoléon. The emperor keeps on marching towards Vienna to, quote "save the Russians half the way", end quote. One must keep his good humour even at war I guess. He did put his money where his mouth was though, taking Vienna on November 15.

The Coalition is still not defeated however, with the Russians on their way under the leadership of general Koutouzov. Napoléon forces the issue by setting up a trap, making his enemies believe that he is weaker than he really is. The decisive battle will be fought at Austerlitz. This name alone still resonates as Napoléon's most astonishing victory.

On the morning of December 2nd 1805, exactly one year after he was crowned Emperor, Napoléon faces both the Russian Tsar Alexander I and the Austrian Emperor Francis II, that's why it became known as the Battle of the Three Emperors. Long story short, Napoléon used the terrain and even the morning midst to lure the Russians and Austrians into attack him where he wanted them, only to counter attack to crush them, under the Sun of Austerlitz, making the midst disappear.

Although the Allies did vastly outnumber the French, around 70,000 French troops against 90,000 allied troops, Napoléon's trap and quick thinking allowed him to win a decisive victory, probably one of the most decisive victories in history actually. The Allied armies are shattered, having suffered terrible losses. The Grande Armée comes out of this battle as the strongest force in Europe. Russia and Austria are defeated, humiliated. Learning of the defeat, William Pitt, the British Prime minister pointed to a map of Europe and stated, quote: "roll up that map: it will not be wanted these ten years", end quote. He knew perfectly what Napoléon had just accomplished. Napoléon himself knew what had been won and said to his soldiers, quote: "Soldats ! Je suis content de vous. Vous avez à la journée d’Austerlitz, justifié tout ce que j’attendais de votre intrépidité ; vous avez décoré vos aigles d’une immortelle gloire." and he concluded "Mon peuple vous reverra avec joie, et il vous suffira de dire « J’étais à la bataille d’Austerlitz », pour que l’on réponde, « Voilà un brave »", end quote. Now for the English translation quote: "Soldiers! I'm happy with you. You justified everything I expected from your fearlessness on the day of Austerlitz; you decorated your eagles with immortal glory" and then "My people will see you again with joy, and you will just have to say "I was at the Battle of Austerlitz", so that one can answer, "Here is a brave"", end quote.

Following this, Austria signs the Treaty of Presbourg on December 26th. It ends her participation in the war and it forces her to lose more territory and to pay immense reparations to France. Russia and Great Britain are still at war with France, but in no position to attack her. This has huge ramifications for Europe. It marks a complete reorganization of German territories. The Holy Roman Empire, an entity that had been around since 962, was de facto dissolved. Napoléon and his allies established the Rhine Confederation in 1806, composed of German states allied to the French. Napoléon makes Joachim Murat, who had married his sister Caroline, Great Duke of Berg. He will also name his brother Jérôme King of Westphalia in 1807. Quick note, nepotism had very, very bad results for Napoléon. His siblings proved to be very ineffectual for the most part. They were as demanding and rough has him, but they didn’t have his brains and they were spoiled by him. The only exception to this is probably Eugène Beauharnais, Joséphine's son, who will have a remarkable career, but I'm getting ahead of myself.

The Fourth Coalition War and the Continental System

The war of the Third Coalition was over with the defeat of Austria. But Napoléon couldn't rest for long. European monarchies didn't accept the new order set by the French emperor in Germany and in October 1806, a Fourth Coalition was established to counter him. This time, Austria was not part of it, but Prussia was, along with Russia, Sweden and Great-Britain, the usual bankroller of the wars on the continent. Their aim remains roughly the same: to beat that damned Corsican upstart and to restore European order as it was before. Can you guess the result, dear listeners? Let me take you trough it quickly.

Let me backpedal a bit first. In early 1806, France had conquer Naples, where a Bourbon monarch reigned, and Napoléon had put his brother Joseph in charge, making him King of Naples. He also made another brother, Louis, King of Holland. When you put this along with the changes in Germany, it makes a good chunk of Europe under French domination in one way or the other. Although Napoléon tried to find an agreement with Prussia in early 1806, even signing a treaty in February, the German Kingdom also entertained discussions with France's enemies. In the end, Prussia mobilizes against France in late Summer 1806 and sends an ultimatum to France: French troops must move back behind the Rhine by October 8th. They don't and war resumes in Europe.

The Prussians try to beat Napoléon at his own game, by moving quickly. But by doing so, they also move alone, without their Russian allies. Napoléon understands what is going on and moves with his usual effectiveness. On October 14th, not one but two decisive battles happen. The first is fought at Jena, where Napoléon completely crushes a Prusso-Saxon force under the command of general Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen. At the cost of around 2,500 Frenchmen, the Prussian and their Saxon allies lose ten times that number. At the same time, Marshall Davout defeats a Prussian army almost three times as big as his at Auerstaedt, about 20km north of Jena. This double victory over the famed Prussian army, France's nemesis only half a century before, is a resounding triumph for the Grande Armée and a testament to Napoléon's skills and aptitude at campaigning and deploying huge armies in the field.

By October 27th, the Grande Armée enters Berlin and Saxony joins the Rhine Confederation. It took Napoléon less than three weeks of campaigning to knock out Prussia out of the war, an incredible feat. His attention now turned to Poland, where he would fight the Russians. Although no as tactically sound as the Prussian army, the Russian army still was a formidable force, and its sheer numbers could prove decisive in an engagement. Bad weather conditions slow the advance of the French troops. There are a few minor engagements until winter strikes. Napoléon had actually ordered the Grande Armée to establish its Winter quarters when enemy movement was spotted. The two armies clash at Eylau, on February 8th 1807.

The French have around 65,000 troops will the Russians have over 80,000. The fight is incredibly brutal and happens in the middle of a snow storm. The two sides are evenly matched for some time and Napoléon fears that he could be beaten. He then orders Murat, the Marshall in charge of the cavalry, to intervene. He actually taunts the Marshall, asking quote: "Will you let us be devoured by these people?", end quote. Murat charges the Russian, along with 12,000 cavalrymen. It is one of the biggest cavalry charges in history. It works, breaking the Russian ranks and forcing them to retreat. But the French victory is both pyrrhic and indecisive. The losses are so horrible that Napoléon stated quote: “If all the kings of the earth could view such a spectacle, they would be less keen on wars and conquest”, end quote. Estimates are around 10,000 casualties and over twice this number for the Russians. A preview of the bloody battles that will take place a century later in Europe.

Napoléon and the Grande Armée actually enter Winter quarters after that and can rest. That's when Napoléon meets Marie Walewska, a young Polish noblewoman. He falls for her immediately. She actually has an agenda, she is sent by the Polish nobles to plead their cause for a free and independent Poland. Although reluctant at first, the emperor will find here arguments... persuasive. Nevertheless, he seemed to have developed a real affection for her. He will accede to her request, once the Russians are defeated. This is done on June 14th 1807 at the Battle of Friedland. On that occasion, the French win a complete victory, inflicting over 25,000 casualties to the Russians and annihilating their army. Recognizing defeat, Tsar Alexander meets Napoléon at Tilsit in July and signs a peace Treaty with him. On that occasion, the Duchy of Warsaw is established, a rebirth of the Polish State. It will be a victim of Napoléon's ultimate defeat in 1815 and will be divided between Prussia and Russia following the Congress of Vienna.

Now that Napoléon has defeated the major continental powers, he has to face his arch enemy: Britain. He knows that he can't invade Great Britain, so he decides to strike economically. On November 21st 1806, he signs the Decree of Berlin to establish what was called the Continental System. He effectively closes European ports to British importations. Britain was the leading industrial power at the time. Thanks to its industries and colonies, it sold raw materials and high quality products to all the other countries in Europe. Napoléon wants to diminish its capacity to finance wars against him, so stopping its trade seems logical. But actually enforcing that blockade on a European scale will prove impossible.

The Peninsular War and the Fifth Coalition

The failed enforcement of the Continental system is, to me, the tipping point of the Napoleonic adventure. Although Napoléon will have other victories, it is at that time that the wind started to blow against him. The events and decision that will flow from that failure will inform the rest of the period, all the way to Napoléon's ultimate downfall in 1815.

Let us look at the situation in 1807. Napoléon is the Master of Europe. He has beaten pretty much everyone on land and either subjugated other countries or make them vassals. He has created a new nobility within France and put his relatives on various European thrones. All this, in five years, coming from a country that had undergone an incredibly violent Revolution and a civil war that lasted for years. It's mind blowing and a testament to Napoléon's skills as a leader and France's capabilities as a country.

I should mention that while Napoléon is campaigning all over Europe, he's still governing France. He gets daily dispatches to keep up to date with the events back home and sends back instruction. The modernized administration he left behind does a great job however and the country runs quite well even with its head of state risking his life on battlefields all the time. It is a testament to the quality of the reforms operated during the Consulat that France kept going for so long despite the enormous stress and demand caused by continuous wartime. However, her stamina was getting taxed a lot and Napoléon was about to embark on an adventure that would cost him much more resources than he expected.

I should also mentioned that Napoléon had help from very hardworking and competent men. Two of the most notables are Joseph Fouché and Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, simply called "Talleyrand". Fouché was Minister of the Police, and he played a key role in the Imperial government. He was ruthless and brutal. A former Jacobin, he will prove instrumental and Napoléon will utilize his services even during the Hundred Days in 1815. Talleyrand, for his part, was Minister of Foreign Affairs... on an on and off basis. He was a diplomatic genius and is probably the reason why France didn't lose more Thant it did at the Congress of Vienna. Napoléon knew and respected that but he also saw him as a weasel, a man with no loyalty who would serve any master for his own advancement. This clash of tempers once prompt Napoléon to say to Talleyrand "You are crap. Crap in a silk stocking". And used a rather stronger word than crap, the one also used by Cambronne in 1815...

Now, Napoléon faced a problem. One country refused to stop importing British goods: Portugal. Portugal had been a British ally for centuries so this didn't come as a surprise, but it frustrated Napoléon. If the blockade was not enforced everywhere, he could not force Britain to negotiate. Therefore, and besides Portugal's final acceptance of Napoléon's demands, the French army invades Portugal in October 1807. Despite a very difficult journey, the French troops under general Junot take Lisbon in late November, forcing the Portuguese royal family to flee to Brazil. This was accomplished with Spain's blessing. The French ally had allowed her army to go across her territory to conquer Portugal. But Napoléon was wary of the Spanish royal family. They were Bourbons, having been put on the throne by Louis XIV. In 1808, Fernando, son of the king of Spain Carlos IV, deposed his father and took the throne, becoming Fernando VII. Carlos asks for Napoléon's help and arbitrage. He conveys both of them at Bayonne in May 1808. Oh he arbiters the situation, by taking the crown and giving it to his brother Joseph, who in turn gives the Neapolitan crown to Murat.

The Spaniards are absolutely furious and rebel against the French in Madrid. They are violently repressed in what has become known as the Dos de Mayo uprising, immortalized on the famous paintings by Francisco Goya. That will be the start of an horrible guerrilla warfare and a series of French abuses, looting, destructions and murders all over Spain and Portugal. A real shame on the French army and Napoléon. He maybe wasn't there, he maybe didn't order the massacres or looting, but he was commander in chief and the buck stopped with him. So as I hold him responsible for the great things accomplished by and under him, I also hold him responsible for the bad ones. The French exactions in the Peninsula are inexcusable.

The whole country takes up arms agains the French and on July 22nd 1808, a French army under general Dupont is defeated at Bailén. A small defeat in the grand scheme of things, but a defeat nonetheless. The Grande Armée was not invincible. The news spreads quickly. Various European countries watch the events unfolding with great interest. Amongst them are Britain and Austria. Britain reacts first, by sending a detachment to fight the French in Portugal. They are led by general Arthur Wellesley. He is better known by the title he is given in 1812: the Duke of Wellington.

The French promise to the Spanish and the Portuguese that if they take over, they will impose Revolutionary ideals of equality and freedom. It doesn't work, men from both countries decide to favour their nations rather than some ideal imposed at the tip of bayonets. The French moral ascendence, if it ever existed, was definitely a thing of the past, whether Napoléon recognized it or not. Later in 1808, he takes over the operations himself in Spain to redress the situation. He succeeds and retakes Madrid on December 3rd. But he has to leave and let his generals handle Spain. Austria is rearming.

The Habsburgs had been beaten repeatedly by Napoléon. Worse than that, they'd been humiliated by him. This Corsican upstart had defeated and impose his will on one of Europe's oldest and most prestigious families. This kind of ego does not go down quietly. Seeing what was going on in Spain, the Austrians decide to try and take their revenge against the French. They cannot count on powerful allies though. The Russians are still technically allied with the French and the Prussians know that they are not ready yet to fight the French. Britain, as usual, sends money, plus keeps the pressure on in Spain. The Austrians had been hard at work reforming and modernizing their army. They think they can take on the Grande Armée and defeat Napoléon.

Under the leadership of Archduke Karl von Österreich, the Austrians move first and quicker than before, attacking in Bavaria, Italy and Poland in April 1809. They are first met with successes, taking advantage of errors on the French's side, commanded by Marshal Berthier. Berthier was a extraordinary organizer and chief of staff, but not a great commander and it cost the French dearly in the Spring of 1809. But Napoléon arrives a bit later and takes the helm. Once again, he proves to be a formidable commander, retaking control of the situation and counter attacking quickly and efficiently. Multiple battles ensue, some going the French way, like at Ebersberg on May 3rd, or the Austrian's at Aspern-Essling on May 21-22. This battle in particular cost the life of Marshal Lannes and was Napoléon's first major defeat. Nevertheless, he plans a new attack to cross the Danube and to crush the Austrians. He finally does so at Wagram on July 5 and 6 1809. The armies in presence are huge, over 160,000 French facing 130,000 Austrians. Nothing of the sort was even imaginable a few decades before. The losses are also staggering, with over 30,000 casualties on both sides. But it is a French victory and the Austrians, exhausted and depleted, have to stop the war. On October 14, Napoléon signs the treaty of Schönbrunn with the Austrian emperor Franz II. In 1810, he agrees to let his daughter, Marie-Louise, niece of the guillotined French queen Marie-Antoinette, marry Napoléon. Wait, what? And what do you make of Joséphine? Ahem, let's go back in time to Paris very quickly.

The marriage between Napoléon and Joséphine was in shambles. Although there is still affection and complicity between the two, the fact that their union cannon produce heirs is a real problem for the Emperor. He's had children with his mistresses, she's had children before. But together, they can't, even after ten years of marriage. So on December 15th, they divorce and Napoléon is free to marry the young Marie-Louise. Joséphine had a huge impact on Napoléon and on France during her lifetime. Her daughter, Hortense, will eventually give birth to Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, the future Napoléon III. Her son, Eugène, will have a remarkable military career and have descendants that sit on various European thrones and sometimes still do. Talk about lasting influence...

To close this chapter, Napoléon will marry Marie-Louise in March 1810 and the couple will have a boy in March 1811, also named Napoléon. He's proclaimed king of Rome and imperial prince, although he will never sit on any throne and die in 1832 of tuberculosis. Nevertheless, at the time of his birth, Napoléon was greatly relieved and he showed great affection for his wife and son until their ultimate separation a few years later.

The beginning of the Downfall: Russia

During the Fifth coalition, Russia had been a very "soft" ally for Napoléon, not providing any real support for his war against the Austrians. Tsar Alexander also doesn't enforce the blockade against Britain, his country just needs the industrial products sold by the British more than it needs a French alliance. By 1811, Napoléon knows that war with Russia is inevitable. So does the Tsar who mobilizes troops on the Polish border. This time, Napoléon wants to take the fight to them and to inflict a devastating defeat to impose his will on the Tsar. He wants a lasting peace, favourable for France and detrimental to Britain.

The French are still entangled in an unending war in Spain. Their takeover of Rome and arrest of the Pope in 1809 did nothing to earn them a good reputation in catholic circles, which are predominant in Spain and Portugal. Napoléon underestimates the logistical needs of a Russian campaign. He's at his most effective in quick, remarkable campaigns. Here, he has to plan months ahead, have depots set up in Germany and in Poland. He also has to incoporate many foreign regiments in the Grande Armée. While he does do that fairly effectively, it still takes a huge amount of time and effort. Also, this newly formed Grande Armée of over half a million men, a first in the world, will prove less flexible and slower than his usual forces.

On June 24 1812, he enters Russian-controlled Poland and starts moving East. His goal was to force the Russian army to fight him and to win a decisive victory. He will never achieve that.

The Russian campaign is often seen as a foolish, impossible endeavour. People compare it to Hitler’s invasion of the USSR in 1941. But I don’t agree. Napoléon did not want to conquer Russia or to make it a lebensraum for France. He also did not have the Nazis’ racial prejudices. He wanted to defeat the Russian army in the field and to impose his will to the Tsar. He actually came quite close to achieving that. But he failed. As we'll see, he'll win at Borodino, but he won't destroy the Russian army. That’s what cost him the war more than anything in my opinion. The rest was just misery and suffering on an unprecedented scale.

There is also a great strategic mistake here in my opinion, from the get-go. The Grande Armée enters Russia in 1812 while the conflict in Spain rages. The French have had to recall troops for the Russian campaign and Wellington took advantage of if to up the pressure. He wins a decisive victory over the French at the battle of Salamanca in July 1812 and enters Madrid a few weeks later. He'll be at the Pyrénées by May 1813. Having a two-fronts war is almost always a mistake, and this is no exception.

While his troops were facing the Spanish, Portuguese and British in the Iberian Peninsula, Napoléon was pursuing the Russians in Poland and then into Russia itself. But the Russians know that they have the advantage, they can retreat almost indefinitely and they do so. They also practice a scorched earth policy, preventing the French from living off the land as they had done in previous campaigns. This proves very effective to slow and weaken the Grande Armée, at the cost of many Russian civilian lives. Finally, after weeks of skirmishes and marching, Napoléon catches up with the Russian army on the Moskowa river and the long awaited battle is fought on September 7th 1812.

On that day, over 300,000 men were present on the battlefield of Borodino. The French win, in the sense that they hold the ground and force the Russians to retreat, but they are not routed. The Russian army retreats in an orderly manner, ready to fight another day. The French had suffer over 30,000 casualties, the Russians over 45,000. Napoléon marches on to Moscow and takes the city on the 14th, without meeting any resistance. The Russians deliberately let the French in. Once they are settled, the city burns. The Russians had prepared a trap, and Napoléon was caught in it. He tried to force the Tsar to negotiate, but to no avail. A month later, he understood that victory had eluded him in Russia and started heading back to France. That's the moment were the real nightmare began.

The Grande Armée was constantly harassed and attacked by Cossacks and other units of the Russian army. Quickly, the mild weather became cold, then the full brunt of the Russian winter hit the French soldiers and their allies. Everyday, men died from hunger, disease or just from the cold. The Grande Armée was dwindling every day. The Russians tried to finish the French off at the Berezina river at the end of November. Over a period of four days, the Grande Armée managed to escape, at the cost of 40,000 men left dead behind. Even to this day Berezina is a common word in French to evoke a debacle. On December 5th, Napoléon heads back to France, were the situation is deteriorating quickly too. He left Murat in charge, but even him would leave after, to go back to his kingdom of Naples. When all was said and done, the Grande Armée was no more, reduced to less than 100,000 troops. Napoléon had lost many of his veterans and skilled soldiers. And with them any hope of defeating further coalitions.

Europe Strikes Back

The Russian strategy had proven victorious, Napoléon was defeated, humiliated and weakened. In 1813, the whole of Europe would take the fight to him and ultimately, to France. First and foremost, the Prussians, who had been throughly defeated a few years before. They had been prudent, waiting for the right moment to strike back, that was it. At first, the French armies manage to fight them off and earn victories at Lützen and Bautzen in May 1813. But the Prussians, the Russians and even the Austrians manage to fight together and Napoléon is defeated in October 1813 at the Battle of Leipzig. Napoléon has lost around 60,000 troops, as well as many generals and even Marshal Poniatowksi. He has to go back behind the Rhine river. By February 1814, the Allies have agreed, no more separate peace this time. They would attack France together, defeat Napoléon and force him to accept their terms this time.

Wellington and the British were entering France from Spain, Austria was attacking through Italy. Even Murat joins the ranks of the Allies, saying that he must defend his Kingdom of Naples before serving his emperor. The whole world was falling on Napoléon and on France. Both of them were exhausted after twenty years of almost continuous warfare. But they still had resources and the will the fight, they would not go down easy. Napoléon even declines peace offerings from the Allies, giving him an honourable settlement. He still thought he could gain a decisive victory and impose better terms. He was deluding himself. When he realized this, it was too late.

In early 1814, the Prussians, British, Austrians, Russians and their allies launch their offensive in what became known as the Campaign of France. Over a million enemy soldiers attack a country now defended by less than 350,000 soldiers, a lot of them being young lads, barely trained. They are known as the "Marie-Louise" conscripts, the decree for their conscription having been promulgated in late 1813 by the empress. They are brave soldiers, but they lack the experience of their dead predecessors in Russia.

It's a paradox campaign. Napoléon defends France with renewed energy and tactical genius. Attacking the Russians, pivoting, attacking the Prussians, or the Austrians. He wins battles in February 1814 at Champaubert, Montmirail, Château-Thierry, Vauchamp and Montereau. But it is all for nothing, the forces are just too unequal. Paris is taken on March 30th 1814. Talleyrand negotiates with the allies and Napoléon abdicates on April 6th. He is to be sent to Elba in Exile, as governor of the island. He's also to receive a pension of two millions of Francs. Louis XVIII is put back on the throne. Napoléon is so depressed at this point that he ingest poison, trying to kill himself. The poison was rather old however and had lost its potency, it makes him very sick but doesn't kill him.

Let me quote what Napoléon said to his men before leaving Fontainebleau in late April 1814. The Emperor said quote:"Soldiers of my old Guard, I bid you farewell. For twenty years, I have constantly found you on the path of honor and glory. In recent times, as in those of our prosperity, you have continued to be models of bravery and loyalty. With men like you, our cause was not lost. But the war was endless; it would have been civil war, and France would only have become more unhappy. So I sacrificed all our interests to those of the homeland; I'm leaving. You, my friends, continue to serve France. Her happiness was my only thought; it will always be the object of my wishes! Do not complain about my fate; if I have consented to survive, it is to still serve our glory; I want to write the great things we have done together! Farewell, my children! I would like to press you all on my heart; let me at least kiss your flag!" - Napoléon then proceeds to hug general Petit and to kiss the flag and then says "Farewell once again, my old companions! May this last kiss pass through your hearts!".

In May 1814, France was once again a Bourbon monarchy. All was back as it was and European order would not be disturbed again for a very long time..... I'm just kidding, this is Napoléon we're talking about! It'd take more than complete military defeat and exile on a Mediterranean island to silence him. The story of his comeback is quite remarkable.

Louis XVIII isn’t exactly popular nor effectual. The French people are also wary of the monarch. Even though they'd been through hell during the Napoleonic wars, they still felt closer to Napoléon than this king, imposed on them by the other European powers. Louis XVIII also refuses to pay Napoléon his pension. Between that and the unstable political situation, Napoléon has the perfect excuse to come back to France. He escapes Elba and lands in southern France on March 1st 1815. This is the beginning of the period known as the Hundred Days.

Over the next twenty days, along with a few men, he will walk and ride all the way back to Pairs. Army regiments sent after him rally to his cause. Famously, on March 7th, soldiers from the 5th regiment of line infantry face him. He gets in front of them, alone, opens his coat and yells: "Soldiers of the 5th! Recognize your Emperor! If there is anyone who wants to kill me, here I am!". They do not shoot, but they shout "Vive l'empereur !" and rally to his cause. The entire army does the same as do most of the generals and Marshalls. Louis XVIII flees during the night of the 20th of March and Napoléon enters the Tuileries palace the next day. He had just retaken control of France, without firing a single shot. I think it speaks volumes about his stature, his personality as well as France’s situation at the time.

The Allies, already gathered at Vienna, have outlawed Napoléon. They declare war on him. Not on France, but on Napoléon himself, even though at this stage, he didn't attack any one. In France, he tries to gain support from the people by reforming the State, making it more democratic, through the Charter of 1815. But it doesn't get much traction. Fouché, who is back in charge of the Interior, anticipates that the Emperor is doomed. So does Talleyrand. Neither men really support him at this stage, at least not completely or truly.

Seeing Europe uniting against him, Napoléon decides to strike first, to attack his enemies before they can unite their forces, like he had done in Italy in 1796. In mid-June, he enters Belgium, hoping to crush the British and the Prussians before the Russians and Austrians can arrive. He achieves surprise and marches on. Ney pushes the British back at Quatre-Bras and Napoléon wins his last victory at Ligny over the Prussians. His enemies have been defeated, but not crushed. They fall back and on June 18th, the French face the allies on the battlefield of Waterloo. Wellington is there, well prepared and entrenched. His ally Blücher is on his way. The armies clash, Napoléon attacks head on, not doing some clever manoeuvre like Wellington had feared. The emperor had famously sent Marshall Grouchy after the Prussians to try to catch them and defeat them. They eluded the Marshal and came to help their British and Dutch allies. Napoléon had fallen into a trap. The Allies had won a decisive victory. On June 22nd, back in Paris, Napoléon abdicates again, this time for good.

The exile on Saint Helena

What the Allies did to Napoléon shows, I think, how much they feared him. They didn't kill him, for fear of making him a martyr. They didn't put him in some jail in England. No, they sent him on a tiny rocky island in the middle of the Atlantic named Saint Helena. Fouché and Talleyrand had arranged for Louis XVIII to come back, to appease the rest of Europe at the Congress of Vienna. This can been seen as a victory for the old, conservative powers over revolutionary France. I often found it funny that Fouché, a Jacobin and regicide, as well as Talleyrand, an apostate priest, where the men who ensure the comeback of traditional monarchy in France. How quickly the wheels can turn... They would turn the other way in 1830 and 1848. The seeds of the Revolution had been sown all over Europe, laid in the soil by French bayonets, but that's another story.

Anyhow, after transiting for weeks on the ships Bellerophon and Northumberland, Napoléon lands in Saint Helena on October 16th 1815. He will live there his last few years, under the uncaring watch of governor Hudson Lowe. Exhausted by years of constant campaigning, he grows sicker and weaker. He dies on May 5th, 1821 from a stomach disease. He had had the time to write his memoirs however, to control the narrative of his adventures, even in death.

The emperor was buried on Saint Helena with an unmarked grave and stayed there until 1840. That's when French king Louis-Philippe, facing a public opinion crisis, managed to negotiate the repatriation of the remains of Napoléon, to be properly buried in France. The French king underestimated how popular the dead emperor still was. People were ready to praise Napoleon and his memory, not the king. On December 15th, 1840, Napoléon's body is brought back in Paris and laid to rest in the Invalides, observed and followed by a gigantic crowd. His porphyry sarcophagus can still be visited there today. Napoléon's journey was definitely over.

Conclusion

The impact of Napoléon on world affairs raises the question of the great men theory. We have two ways of seeing history: either has a series of events punctuated by the emergence of great men, or has a continuum with very deep roots that cannot be truly changed by any given individual. Some individuals will maybe channel an important change and make it happen, but they aren't truly responsible for it. This is the stance taken for example by the École des annales, an approach of history pioneered by French historians Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre in the 1920s. It takes a rather global and culture-oriented approach. The opposite, old-school way of seeing history that I mentioned, is more focused on the leaders, the men and women responsible for various acts or decisions.

My take? I do believe that deep roots and culture are essential in understanding a situation. The French Revolution doesn't result of any given individual's actions or decisions. Not even the French absolute monarch can be held directly responsible for the events that shook France in 1789 and after. Napoléon himself would never have had the success he encountered if he'd been born a couple decades before. Napoléon needed the Révolution to become who he became. But at the same time, his drive, his will and his intelligence do not fit in any historical model. He's a disturber, probably the greatest disturber of his era. So, while one cannot go back to the "great men of history" theory totally, one has to acknowledge that some men and women are, truly, extraordinary, in the literal sense. They bring something to the table that nobody else does, and their presence alters the course of history, for better or worse. Napoléon is, in my view, one of these people.

The Corsican Ogre for some, the Great Emperor for others and finally, the Petit Caporal for many of his men, Napoléon remains a fascinating figure, no matter how you look at him. The wars that he fought, the reforms that he made, the modernization, the profound change of the European order, all these are still with us today. I don't mind if you see him as a hero or as an antichrist, as a bloody dictator or a great statesman. He's a man worth studying, worth learning from, from both his accomplishments and mistakes. He's a man who nobody should ignore. Huh, who am I kidding, I even said it in my introduction. Everybody, absolutely everybody knows Napoléon. Though, hopefully, now you know why.

Thank you for listening, au revoir.